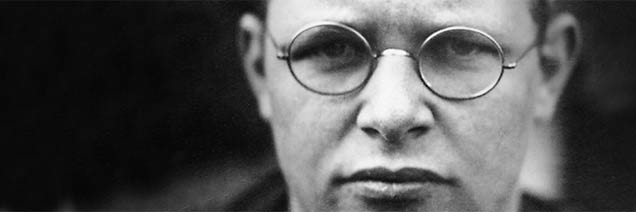

Reading Letters and Papers from Prison, I was surprised to discover Dietrich Bonhoeffer used the sign of the cross in his daily prayers.

“I’ve found that following Luther’s instruction to ‘make the sign of the cross’ at our morning and evening prayers is . . . most useful,”

he said in one letter.

“There is something objective about it. . . .”

Growing up evangelical, I always understood signing oneself to be empty superstition. It was something Catholics did, not Protestants. And yet here’s a famous Protestant pastor and theologian comforting himself with the sign while imprisoned.

Not to mention Martin Luther instructing every Lutheran since his own day to “bless yourself with the holy cross,” as he says in his Small Catechism. Owing to my ignorance, this was also a surprise. But in fact the German Reformer directed the sign’s use not only for morning and evening prayer, but also for baptisms and ordinations.

Adding to my curiosity, in the same letter Bonhoeffer cautioned, “[D]on’t suppose we go in very much for symbolism here!” And also said this: “[M]y fear and distrust of religiosity have become greater than ever here.” According to my upbringing, the sign of the cross wasnothing but symbolism and religiosity. Yet Bonhoeffer signs himself. Why?

Spirituality is physical

To begin with, signing oneself is more than mere symbolism. It is, as Bonhoeffer said, “objective.” There is something tangible and actual about tracing the points of the cross over one’s body. It goes back to something covered in C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters. Christians, the senior demon informs the junior, “can be persuaded that the bodily position makes no difference to their prayers, for they constantly forget . . . that they are animals and that whatever their bodies do affects their souls.”

What we do physically affects us spiritually. Whether it’s lowering our gaze, raising our hands, bending our knee, or crossing ourselves, physical actions have a qualitative, spiritual effect.

Next, signing oneself is more than mere religiosity. It’s communion with God. At bottom, the act of faithfully signing the cross is an act of prayer, one that is physical, a remembrance, a benediction, a collect that gathers every trial, worry, and fear and consigns it to the care of Christ. It can also be used to express gratitude at a meal, joy at a blessed occurrence, repentance in a moment of sin, resistance in a moment of temptation, and faith when undertaking any task (with emphasis on any).

It’s always been this way in the church. “At every forward step and movement,” Tertullian wrote in the year 204, “at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign [of the cross].”

Declaring our true identity

This is not some superstitious innovation of the Middle Ages or the empty religiosity Bonhoeffer opposed. It’s a foundational aspect of Christian identity. Making the sign of the cross says to yourself (and anyone watching) that you belong to Jesus, that you belong to God. When faced with temptation, wrestling with a bad attitude, or feeling grateful for the mercies of God, is there anything better?

Identifying as Christian by using the sign of the cross is a physical and demonstrative way to communicate our reliance on God and our identity in Christ.

Today I make the sign of the cross when I pray, when I’m tempted, when I drive, when I walk, when I’m thankful, when I face something horrible or difficult. It didn’t come naturally at first. I felt very self-aware and hesitant. But the more I did it, the more I came to cherish—even need—to cross myself. For any believer, whether Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox, such a confession is the furthest thing from superstition. It’s a helpful step toward serious devotion.

Christ bore the cross for every needful thing in our lives, and we demonstrably acknowledge as much in its sign. Bonhoeffer said the sign of the cross was objective,

“and that is what is particularly badly needed here.”

Here, too.