by Matt Walsh

In one of the creepiest yet most revealing Twitter threads ever to be posted on the platform, a teacher recently fretted out loud that virtual classes might allow parents to hear him brainwashing their kids. Matthew R. Kay, an educator and author of a book on “how to lead meaningful race conversations in the classroom,” worried that “conservative parents” would be able to interfere with the “messy work” of indoctrinating children into critical race theory, gender theory, and other left-wing dogmas.

Here’s the entire thread, which has since been set to private:

So, this fall, virtual class discussion will have many potential spectators — parents, siblings, etc. — in the same room. We’ll never be quite sure who is overhearing the discourse. What does this do for our equity/inclusion work?

How much have students depended on the (somewhat) secure barriers of our physical classrooms to encourage vulnerability? How many of us have installed some version of “what happens here stays here” to help this?

While conversation about race are in my wheelhouse, and remain a concern in this no-walls environment — I am most intrigued by the damage that “helicopter/snowplow” parents can do in the host conversations about gender/sexuality. And while “conservative” parents are my chief concern — I know that the damage can come from the left too. If we are engaged in the messy work of destabilizing a kid’s racism or homophobia or transphobia — how much do we want their classmates’ parents piling on?

It’s important to note that while some teachers responded to Kay’s comments with the appropriate level of horror and disgust, many others chimed in to share their own strategies for brainwashing during a pandemic. One teacher said she’d also been “thinking about” the problem Kay described, and had decided that she’d ask students about their preferred pronouns via survey — though she still worries that “caregivers” might see it and learn something about their children that they weren’t supposed to know.

Another teacher said that students last semester would sometimes “type secrets into the chat” whenever the discussion turned to “anti-racism and gender inclusive content.” Another complained that a white parent— she made sure to specify “white” — in her district recorded a Zoom class and “filed a complaint against the teacher for an anti-racist read aloud (saying the teacher’s commentary was inappropriate and biased).” This, the teacher says, “is going to be an issue.”

A ninth grade teacher shared in the commiseration, saying that her class required students to “read and respond to a news article,” but that participation in this exercise is stunted now because “outsiders” are “listening.” The “outsiders,” to be clear, are the children’s parents. A teacher with pronouns listed in her Twitter handle said that she plans to use the chat function more than voice lectures because she wants children to share “information” with her in a “parentless way.” A science teacher agreed with all of the sentiments expressed here and summarized it bluntly: “Parents are dangerous.”

A ninth grade teacher shared in the commiseration, saying that her class required students to “read and respond to a news article,” but that participation in this exercise is stunted now because “outsiders” are “listening.” The “outsiders,” to be clear, are the children’s parents. A teacher with pronouns listed in her Twitter handle said that she plans to use the chat function more than voice lectures because she wants children to share “information” with her in a “parentless way.” A science teacher agreed with all of the sentiments expressed here and summarized it bluntly: “Parents are dangerous.”

And these are just the comments that were captured in screenshots before the tweets were all made private. Presumably, there is more where this came from. A lot more.

Several points must be made in response.

First, classrooms are certainly not “safe places” for children to be “vulnerable.” Students may say and do things when they are with their peers in school that they would not say and do at home, but only a fool who doesn’t understand the first thing about child psychology and the effects of peer pressure would assume that the child’s at-school version of himself is the most authentic, much less the most healthy. The pressure to conform to the values and opinions of your peers in the classroom is immense, and often suffocating. There is a reason why rejection and alienation by peers has contributed to a true epidemic of suicide among young people.

The very same people who extol the classroom as a “safe place” for vulnerability will also tell us, on different days and in different contexts, that bullying is a major problem for today’s youth and many of them are driven to self-destruction because of it. So, which is it? Is the classroom a place for open and genuine dialogue, where children can safely express their truest feelings and beliefs, or is it a place rife with bullying and mockery, where rigid conformity is demanded and those who fail to meet the demands are severely punished? It certainly can’t be both.

Second, an adult keeping a secret with a child, and helping the child conceal that secret from his parent — especially when the secret has anything to do with sexuality — is acting in a way that is nothing short of predatory. If you heard a strange man on the playground whisper to your child, “this will just be our little secret,” you would assume that the man is some kind of sex offender. Does this behavior suddenly transform from disturbing to admirable if the strange man is a teacher? No, it doesn’t. But this is the sort of license society has given to teachers, on the the theory that they cannot do the work of educating unless they have more power over, and intimate knowledge of, their students than the students’ own parents.

That brings us, finally, to point three, which is that a public school teacher is not supposed to be, and should not try to be, educator, parent, shaman, spiritual guide, therapist, friend, confidant, and sex counselor, all rolled into one. He or she is meant to fill only the first role on that list, and only in the subject the teacher has been assigned to teach. A child’s actual parents only come to be viewed as “dangerous” interlopers and intrusive “outsiders” when teachers begin to view themselves and the school system as the true guardians and conservators of the children that are temporarily in their care. And that, ultimately, is the problem with the modern education system.

Children are not old enough to be emancipated. They cannot yet go out and live their own lives. They cannot make every decision for themselves. They must belong to someone — not owned like objects but cared for and protected like the vulnerable human beings they are. The fundamental question is who do they belong to. Different cultures in different times and places have had different answers to this question.

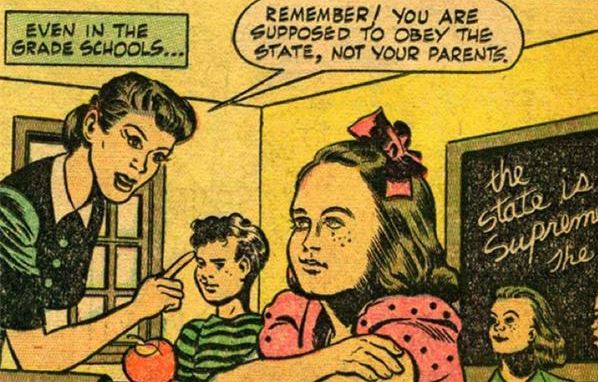

Here, in contemporary American society, there are generally two ways of looking at it: children belong to their parents, or they belong to the school system (which is to say, the government). In one vision, a child is a son or daughter, in the other, the child is a ward of the state.

Only one of these visions is healthy, natural, and humanizing. Only one can properly facilitate a child’s emotional, mental, intellectual, and spiritual growth. The school system doesn’t just have a wrong and harmful idea of what education is — it has a wrong and harmful idea of what a child is, and what its fundamental role in a child’s life is supposed to be.

And that is why I will not send my kids into its clutches.

Neither should you.