by Edith M. Humphrey

The editors of Orthodox Life offer to their readers an edifying reflection on the Church’s response to pastoral and theological questions regarding sexual morality and Orthodox anthropology.

We believe that this will not be a final word, but rather one of many statements of encouragement and direction to the faithful.

Introduction

This week, two publications caused consternation among Orthodox Christians who frequent social media. The first was the electronic publication of a foreword by Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) to the latest issue of The Wheel. This issue, entitled “Being Human,” includes articles by Orthodox clergy and academics on the debate concerning anthropology, sexuality and related concerns. A few articles have already been published online, but the complete issue has yet to be released. The second post appeared online in response to His Eminence’s foreword. It was entitled, “Kallistos Ware Comes Out for Homosexual ‘Marriage.’” Accompanying the article was an alarming photo of the Metropolitan sporting a photoshopped “gay pride” button — a creative touch that has since been removed.

The second article spread like wildfire through various discussion groups on Facebook, eliciting hot responses on various sides of the sexuality issue and causing at least some to read either or both posts for themselves. It seems that a response to both articles is warranted.

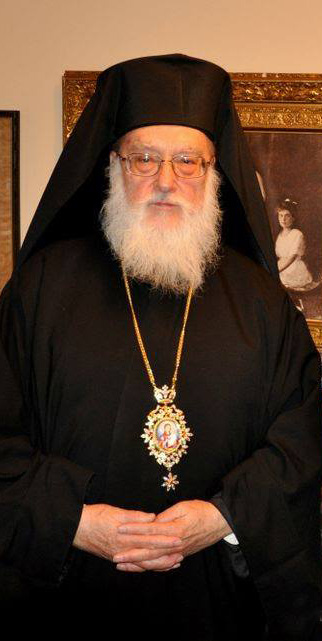

Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia.

With regards to the article that targeted the Metropolitan, I have this to say: if those faithful to the Church’s teachings would represent the truth carefully, without exaggeration, then they would not be discredited. This article’s headline is inflammatory and the photoshopped picture simply deceptive. The metropolitan did not approve gay marriage in his foreword, nor does he wear symbolic paraphernalia. The article does quote accurately from his piece and it is this material that should be considered. To go beyond what the Metropolitan writes, however, allows for a simple dismissal of Orthodox concerns based on the headline’s inaccuracy alone. St Paul’s second epistle to the Corinthians, with its model to avoid cheap and dishonest methods of argumentation, is essential if conservative Orthodox Christians are to avoid being dismissed as fear-mongers, “fundamentalists,” and knee-jerk reactionaries.1 Those posting at Orthodoxnet.com may think that they are rallying the faithful but their methods are counterproductive.

This being said, we must examine the offending article with care and courtesy. We are considering the words of a bishop who has influenced many to embrace Orthodoxy and who has taught us many things. The Orthodox Church was key in my earliest catechesis, and since that time the few personal encounters I have had with Metropolitan Kallistos have shown him to be a compassionate pastor and exhilarating thinker. Therefore any criticism that follows I offer with great reluctance and sadness.

The Faithful Need Clarity

My first concern is that this foreword is ambiguous at a time which cries out for clarity. Leading questions are helpful in the context of the classroom when we are dealing with unexplored territory. And there certainly are matters concerning anthropology and marriage that have not been thoroughly explored in the Church — e.g., How it is that male and female, separately and together, are made in the image of God; whether masculine and feminine are bigger realities than the physical male and female; what kind of continuity and discontinuity might there be between what we are now in our gendered conditions and what we shall be in the Age to come; why does our Tradition only allow the ordination of certain men to the priesthood, while females are more typically considered prophets and mothers; why it is that a godly marriage points to the mystery of Christ and the Church. My prayer has been that the challenges we now face over sexuality will help us to go deeper into these mysteries, just as the Arian and other Christological heresies led to sound and careful explication of dogma. So questions are worth asking: I agree with Fr John Behr and Metropolitan Kallistos that anthropology is one of the major areas of contemplation before us today, and that “silence is not an answer.” But the type of questions matter, especially at a time when the faithful are looking for pastors and teachers to encourage them rather than disquiet them concerning what they have been taught are settled matters — settled since the time of the Bible and the Church fathers.

The Metropolitan sets up two hypothetical situations in the confessional: one man is tempted to frequent gay bars and enter into one-night stands, repents in the confessional, and is restored (and this repeatedly); another lives in a “committed” same-sex relationship but is not prepared to separate or even to give up homosexual activity. The author asks if it is right that the second should be excluded from the chalice but not the first, since the second is at least not living out a cyclical life of promiscuity. To this question the Metropolitan responds, “Something has gone wrong here.” Actually, it seems that it is his characterization of the two scenarios that has gone wrong. The first person is described as promiscuous, rather than as repentant (though weak); the second is described as “committed to a stable and loving relationship,” rather than as resistant to the Church’s teaching. Note that he will not even try to abstain from fornication. There is also an alarming footnote that suggests that in the Church of Finland this second man would not be asked to refrain from communion, as though this is something to be emulated. The Metropolitan, then, is asking a leading question, “Is what goes on in the confessional fair or good?” and he answers it for the reader in the negative.

A proper view of celibacy

Another question that is asked is whether it is right to “put the heavy burden” of celibacy on those with homosexual inclinations. This question only makes sense, it seems to me, from the presupposition that a life without sexual activity is a burden that can only be carried by a few. But the Christian faith requires it of many — of the unmarried, of those married in difficult situations where there is no affection or when the spouse cannot fulfill sexual needs, of those who are separated from spouses in difficult situations, of those whose spouse has died and for whom there is no possibility of remarriage, for whatever reason. It is the world that tells us such a life is not worth living. But if we are, as the Metropolitan says, becoming human and following the pattern of Christ, then such a situation offers a special opportunity for bearing the God-Man’s image. It is a blessing, however difficult it might be. Moreover, it offers strength to the Church as a whole.

This is a place, of course, where those of us who are unabashedly conservative might rethink our normal understanding and allow it to be chastened by Holy Tradition. We tend to characterize the human norm as a married state, but instead we should thank and encourage our celibate brothers and sisters for we need their witness no matter what circumstance leads them to this place. As Jesus explained, there are many causes of being a “eunuch” but this can be done for the glory of God!2

Are the Church’s teachings invasive?

Next, the article asks us to consider why we put so much emphasis on “genital sex,” and whether it is seemly for the Church to “peep through the keyhole” to see what others are doing. This is prefaced by the remark that there are many good things to see in a committed same-sex relationship besides the sexual intimacy. But the problem here is at least twofold. First, there is a structural sin in the coming together of two same-gendered persons, for it rejects the primal statement, confirmed by Christ, that in the beginning He made them male and female.…3 There is no doubt that two such persons can show compassion and sacrifice towards each other. But already the character of their relationship is skewed, for what they are enacting is a parody of God’s purpose. Such a relationship cannot be simply a matter of friendship plus sex, where we could approve of the first but question the second, as though they were separate matters. What is done in the body affects the spirit and the soul.4

Secondly, the Church does not peep through key-holes at a private event entitled “genital sex” — as if that is all there were to physical intimacy! The tenor of the Scriptures, the discipline of the Church, the care of the confessor all teach us that intimacy goes beyond this one kind of contact. Furthermore, our romantic lives are not simply our own business, but rather effect one’s own body (the temple of the Holy Spirit), the other partner, and everyone else in the Body of Christ.

Besides this, we must not be naïve about the current situation. We are no longer being asked to overlook what is happening “in private” but to celebrate and honor a relationship based specifically on its same-sex foundation. Indeed, some are claiming that such relationships are in themselves a viable route to theosis, and therefore should be blessed by the Church. The days of “don’t ask, don’t tell” are long gone in most quarters; and were they ever helpful so far as true spiritual guidance was concerned?

Asking the right questions?

Finally, there is the conclusion of the piece. The Metropolitan makes the disclaimer that he is not suggesting we abandon Orthodox teaching on this matter wholesale, but rather that we “enquire more rigorously into the reasons that lie behind it.” I would have welcomed a foreword that actually did this, raising questions regarding anthropology, discipline, and sexual expression. Instead, His Eminence’s questions have led the reader to question the ability of Orthodox Christians to discipline their bodies, the wisdom of the confessor who is seeking the salvation of those who have same-sex desire and whom he loves, and the dignity of a Church that cares about sexual expression among its members. Indeed, he does not only commend an inquiry into the reasons for the Church’s teachings, but also “experimentation,” “creative courage,” and “loving compassion” that “acknowledge…the variety of paths that God calls us human beings to follow.”

I have seen this kind of rhetoric before and it leads in only one direction. What begins as a call to pastoral clemency frequently ends in an unexamined shift in ethical and social practice. In contrast, I would agree with my dear friend Bradley Nassif, who quotes Chesterton’s sage comment that one should never tear down a fence unless one knows why it was put there in the first place. His own article in this same issue of The Wheel, now available to all online, goes far in asking and answering the right kinds of questions, including why the Church, following the Scriptures, has set these boundaries. May the questions we ask come from a place of knowledge and faithfulness, and may those who lead us couple pastoral compassion with truthful discipline. For true co-suffering love requires both!

About the Author

Dr Edith M. Humphrey is the William F. Orr Professor of New Testament at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and Secretary of the Orthodox Theological Society in America. Her latest book is Further Up and Further In: Orthodox Conversations with C.S. Lewis on Scripture & Theology.

Dr Edith M. Humphrey is the William F. Orr Professor of New Testament at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and Secretary of the Orthodox Theological Society in America. Her latest book is Further Up and Further In: Orthodox Conversations with C.S. Lewis on Scripture & Theology.

Source